The Land Trust as an Actor of Change

What is this

This is a proposal for the Boise Community Land Trust (Boise CLT), a nonprofit organization that aims to permanently solve Boise's housing crisis, and transform Boise's landscape of highways, houses and hedges into a city of opportunity, sustainability and social joy. First I'll lay out the goals, then explain why those goals are good, and finally propose a some ideas for how we can make this happen.

1. Mission

The mission of the Boise Community Land Trust is to create quality housing to support an urban middle class without requiring continuous government subsidy.

Affordable: We provide housing for people earning 60-80% of the Area Median Income (AMI), which in Ada County is currently \$73.6k for a family of 4. Over time, the financials of a land trust model will allow us to increase our target range to people earning <60% AMI.

Quality: A CLT has an investment horizon unlike any private real estate developer. Because we don't need to enrich private investors, we can afford to build housing that will serve as a cultural hub and pride of their neighborhoods for hundreds of years.

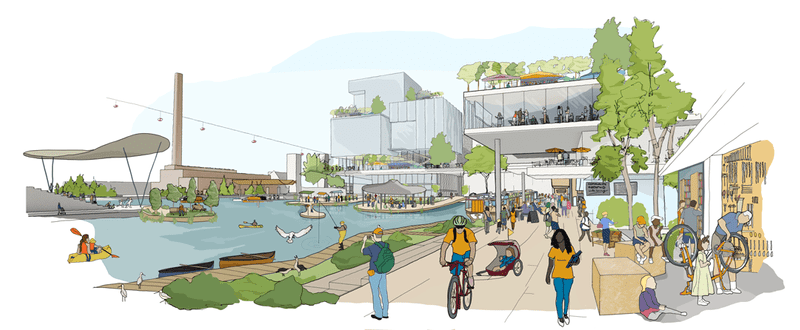

Urban: We build transit oriented development (TOD), which means at densities of at least 30 units per acre and in areas where residents can reasonably live without owning a private vehicle. Currently, this likely limits us to areas within walking and cycling distance of downtown.

2. Why not just build units?

Building housing for our most at risk populations is obviously a moral good, but we have an opportunity to affect Boise's future in ways that extend far beyond warehousing our low income residents. I want to talk about these benefits.

2.1 The case for urban housing

Our prevailing culture would assert that the "concrete jungle" of urban centers is crime ridden, ugly and somehow not natural. Of course, none of this is true, but the sentiment is reinforced by two factors:

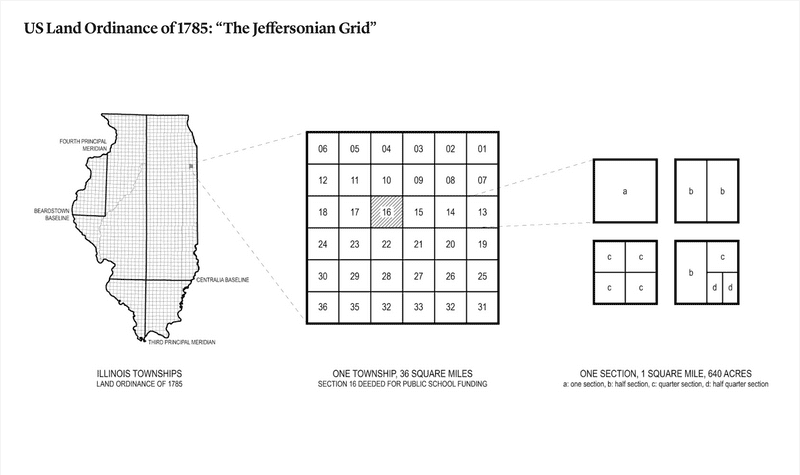

- Our inherited Jeffersonian idea of parceling out the West so that every man may enjoy his own plot and the prosperity that presumably comes with it.

- Our propensity to build urban environments with suburban ideas, which has kept our cities from realizing the benefits of density, and given most Americans a false idea of what city life is like. We must only look abroad to see that with a few changes, something much better is possible.

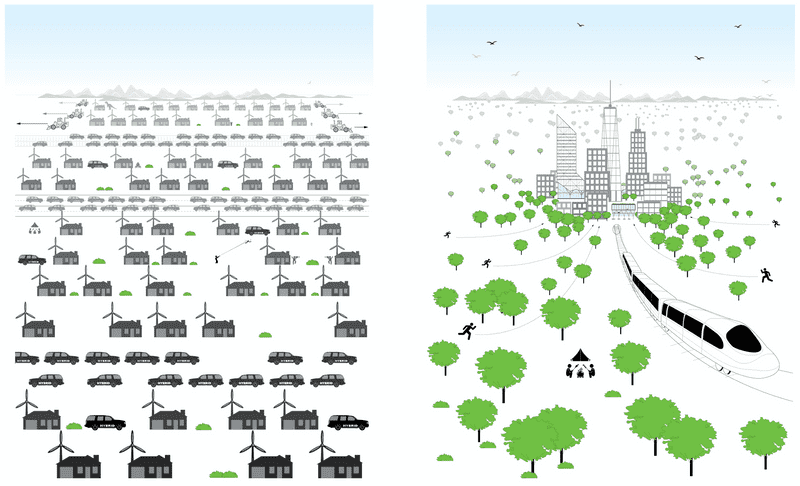

While it is true that land ownership is deeply tied to the American Dream, the suburban manifestation of this principle is largely a creation of 'big government': an explicit policy of mortgage deductions, zoning entitlements, and expenditure on automobile infrastructure. Without government intervention, it turns out, humans tend to live close to each other. Low density living isn't evil, but Boise is a city, and continuing to encourage suburban ideas will allow the benefits of city life to pass us by.

2.1.1 Prosperity and Opportunity

Across the board, density is positively correlated with higher rates of innovation per capita, higher income, more job opportunities, and much lower infrastructure cost per capita. And that doesn't account for the better health, lower crime and other benefits that urban residents enjoy. While prosperity should never be the only measure of value, urban living is pointedly more prosperous and opportunity rich than suburban living - for both the local government and the residents.

2.1.2 Sustainability and Nature

Adopting an urban lifestyle is by far the greenest and most sustainable choice one can make. Urban residents live environmentally friendly lives largely by default. More efficient heating, cooling, and municipal services. Less, and greener transportation, reduced land impact, lower energy use. The list goes on. Living in moderate to high densities is the most impactful way to reduce our environmental impact. Not to mention that the less we sprawl, the easier it will be to access the nature that surrounds us.

2.1.3 The biggie - our transportation problem

Land use and transportation are two sides of the same coin. We are hamstrung to ACHD on transportation, so our only lever of influence is land use - which can be quite effective. A transit-oriented CLT may be the most powerful transportation investment we can make as a city.

It may be possible for a CLT to build 100 (or more) units of mixed income car-optional housing every year without requiring millions in government vouchers that ultimately end up in developer pockets. We pair these developments with appropriate TIF zones, build commercial space into the ground floor, and as the neighborhood prospers we gain leverage to ask for safe, car-free transportation infrastructure.

2.2 But affordable housing has failed?

"Once all the poor have been forced out, as has happened in most European capitals, the city becomes more cultural artifact than cultural hotbed, more museum than metropolis" - Vishaan Chakrabarti

America has a checkered history of affordable housing development. While the 1960s Johnson administration saw leaders such as Edward Logue build many thousands of government owned low-income housing units, many of these projects would ultimately be condemned and torn down, and in popular sentiment, our great experiment in public housing fell alongside them.

Projects like St. Louis' Pruitt-Igoe and Chicago's Cabrini-Green were designed with Le Corbusier's celebrated tower-in-the-park typology which prescribed height in the interest of creating green space around the buildings for community enjoyment. In practice, however, many of the projects suffered from poor management and maintenance, and an "orientation towards the automobile such that the 'park' was actually a parking lot" (Chakrabarti). Not to mention the racial discrimination and class separation intentionally built in to these vast projects. In retrospect, it should be no surprise that a community will suffer if made to live in a desert of opportunity, and encouraged to distrust one another.

While these examples have been politically weaponized to curtail federal investment in public housing, we have also seen that if cities do not provide affordable options for housing and transportation, people will choose instead to live in the suburbs, and all of the economic, social and environmental benefits that are within our reach will pass us by.

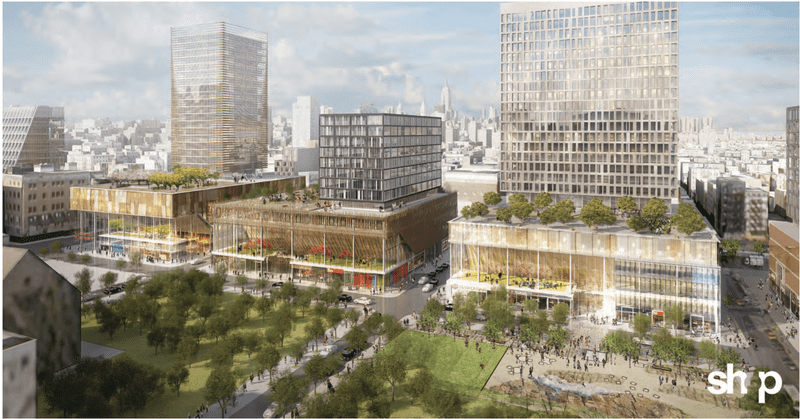

The Community Land Trust model is a significant departure from public housing of the 60s. It does not simply aim to provide shelter for the poor, but is a means to create community wealth and ownership over our built environment. It benefits from financial independence, thereby protecting funds for maintenance and community health from shifting policy objectives. And in this vision for the Boise CLT, we learn from failures of the past by working to build mixed income housing that integrates and benefits already successful communities. Some of these ideas are new, but we rest on the backs of impressively successful organizations like the Champlain Housing Trust of Burlington, VT, which now owns more than \$330M of affordable housing. By providing affordable urban housing under the land trust model, we will create a stable, lasting and community-owned solution to multiple simultanous urban pains.

The CLT Principle: When municipal land is privately owned - which almost all of ours is, its explicit purpose is as a profit center for investors. A CLT functions on the belief that some local land should have the higher purpose of community enrichment, enjoyment and preservation. We use the economics of ownership for social good instead of private wealth.

2.3 What is with the emphasis on quality?

When building affordable housing, one always has to balance the desire to build many units with the other goals of the project. Building high quality units will necessarily reduce the total number we are able to provide. In places like New York City, where real estate prices are so high and affordable housing demand has grown far faster than the housing supply has, lawmakers have little option but to construct as many units as they can as quickly and cheaply as possible. They waited too long and now are stuck with the least bad option. Boise, on the other hand, has a much smaller housing gap. If we get started on this now, we still have the economic opportunity to do more than just build units. That may not be the case in another 30 years.

While the first answer is because we can, the second answer is because we need to. We can expect to be met with resistance when trying to build an affordable apartment building in any neighborhood close to downtown. We will need to build something beautiful that will benefit the neighborhood, not the eye sore they will be expecting when they hear "affordable housing". To foster community support, we will need to operate with the explicit goal of benefitting the surrounding neighborhood.

Why not start with something less ambitious? Because incrementalism in urban issues doesn't work. Usually in politics there is a narrow window in which one can drive a lot of change. Fail to solve people's problems in that time, the window will close, and the incremental changes we made will be labeled failures. We'll be worse off than when we started.

3. Ok, so how?

A CLT is a financially powerful tool for accomplishing our goals, but in order to get to a meaningful scale, we will need to pursue many sources of financing, and utilize every advantage to minimize unnecessary costs. Below I summarize a few of my ideas.

I have made a financial Pro Forma based on some very rough assumptions, and I believe that with municipal support, a CLT apartment building should be able to achieve at least a 5% yield on cost, which would mean about \$700k generated per year that can go directly toward constructing a second project. Under the right conditions, in the next ten years we could contribute 1500 units of urban housing in iconic buildings that will last centuries. Depending on the specifics, it may be possible to achieve even a 15% yield on cost, allowing us to build at least 3x as many units or provide them at a lower rate.

3.1 Federal Financing

Many federal financing options exist for affordable housing. Most of these are accessed through the IHFA.

- Low Income Housing Tax Credits: These are the primary financial tool for affordable housing development.

- Community Development Block Grand Program (CDBG) and HOME: Grants to state and local governments with set asides specifically for nonprofits constructing affordable housing.

- Federal Home Loan Banks (Freddie Mac, Fannie Mae, etc): Provide grants and low interest financing for affordable housing development. They also are beginning to purchase non traditional CLT mortgages (individuals don't own the underlying land, but still build equity)

- Tax Increment Financing: Has been used in Oregon, Florida and Minnesota to financing CLT development. It can be especially powerful in Boise due to its ability to give CCDC some power over ACHD projects. State legislature is clearly skeptical of recent TIFs, but the case for them around a CLT development is strong.

- Housing Bonds: State and local governments can issue low interest, tax free housing bonds for low cost financing.

3.2 Municipal Help

City support will be one of the largest factors determining whether we can get the CLT to scale or not. There are multiple avenues for the city to have an impact:

Financing

- Grants will be necessary in the early years of development. As the CLT matures and pays off its loans, it will be able to grow with limited municipal financing.

- Real Estate: Providing real estate or engaging in real estate swaps will make the CLT self sustaining much, much faster.

- Housing bonds: State and local governments can issue low interest, tax free housing bonds.

Planning and Zoning

Working closely with Planning and Zoning will also be necessary and impactful. We will need to rezone certain areas with density bonuses, reduced parking requirements, and streamlined processing. Furthermore, PNZ involvement will be critical for choosing economical building sites as well as during community engagement.

Staff support

Starting the CLT will involve a lot of operational work, from conducting research and forming a specific plan, to applying for grants from IHFA, developing the project, and then running continued operations. Working together with city staff may be a cheap way to help the CLT prosper initially, and assist with the long term financials.

ACHD

Having spoken with ACHD about increasing the non-car transit infrastructure in Boise, one of the main responses I have gotten is that Boise is too expensive to live in, and they have an obligation to spend their money not on the lifestyle of privileged Boise residents, but on the low income folks who need to live farther out and drive to work. At least one employee, who wields a lot of power within ACHD, has blamed the City of Boise for these conditions. With this in mind, we may be able to work together with ACHD to get some non-car infrastructure investment if we can show a dedication to building affordable housing. We can hope.

3.3 Creative Ideas

3.3.1 Mixed Income + Mixed Use

Most affordable housing experts suggest we put government support behind mixed income housing projects, which are better for residents and for the city. In this scenario, there would be some proportion of market rate apartments, which means the land trust can expand more rapidly due to the increased revenue. Further, increasing the stock of market rate housing near downtown will impact overall affordability as well as our transportation goals.

Depending on the site, a mixed use construction would have commercial space on the ground floor for local businesses that serve the community and will compound the effectiveness of TIF zones.

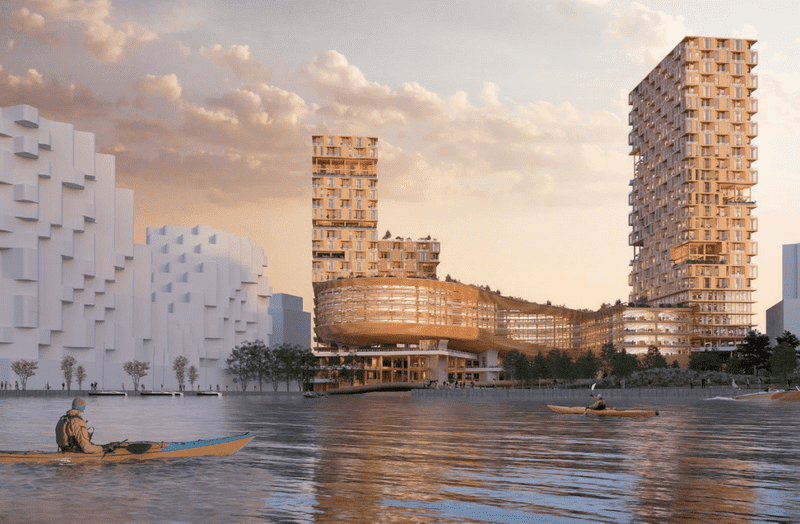

3.3.2 Modular + Mass Timber Construction

Modular construction has the potential to drastically reduce construction costs while improving quality and environmental characteristics. I will be taking a tour of Indie Dwell next week, which might be a great option. Another possibility is Mass Timber, which is a new construction technique to build tall buildings using prefabricated timber components instead of concrete or steel. It has many benefits, including reduced costs and being carbon negative - it actually removes carbon from the atmosphere. Further, since it is a modular construction technique, we can create many distinct buildings using the same fundamental components, which will allow us to reduce costs even further over time.

Mass Timber has been in use with great success around the world, but is currently held back in most US states by a lack of producers and building codes that have not adapted to the technique. However, buildings have been approved and successful in Oregon and Washington, and the codes are beginning to change nation wide.

Mass Timber construction would pose challenges around code approvals as well sourcing the components and construction expertise. However, creating a mass timber business in Boise is also a huge opportunity to create high quality jobs in a proven, green technology that promises to become very popular across the United States in the next decade. I have spoken with friends in the forestry and glue-lam construction businesses, who have indicated they're interested in the opportunity. Forestry companies in other states have even demonstrated a willingness to subsidize initial projects in order to encourage code changes that make their business possible.

3.3.4 Transportation Share

Constructing parking is out of alignment with our goals of decreasing car dependency, and it is also prohibitively expensive, costing about \$60k per space to build underground. We need to find creative ways to reduce car dependency of our residents. One way is through transportation share. This idea requires more research and development, but we could use a car share program where CLT residents have a small number of utility cars available on premises, like a truck and a van, which they can easily rent when they need to use them. We could also provide e-bikes, cargo bikes, mopeds, or other human-scale transportation to make it easy for residents to live there without a car.

This program could take the form of a homegrown solution, a partnership with existing car and bike share businesses, or a combination of both. Not everybody in Boise can currently live there without a car, but the benefit of having a housing shortage is that there is high enough demand that we likely won't have a problem finding residents who are willing to give up a car for the opportunity to live in beautiful affordable housing near downtown.

3.3.5 Robotic Parking

We will, of course, have to build some parking, but creating a parking lot instead of a park in front of the building is hardly in line with our goals. Building underground, meanwhile, costs millions because of all the wasted space needed to get cars into and out of their spots. Developers in Europe and Asia have solved this issue by using robotic parking garages that efficiently store cars underground for half the cost. This is another idea that would require more research, but it could ameliorate the costs of building parking.

4. Next Steps

This is a more complicated proposal than building a standard apartment building somewhere, but it stands to benefit Boise across multiple municipal goals for years to come. From what I can see, the next step is to put together a working group and work with a consultant with land trust experience, such as the Grounded Solutions Network, to conduct some market research and create a more concrete five to ten year plan. Simultaneously would could be forming the nonprofit, selecting an appropriate site, and beginning the process of grant applications.

5. References

Some text and ideas from "A Country of Cities" by Vishaan Chakrabarti, with permission.

Images from Sidewalk Labs, LLC, ThinkWood.com, and around the web.